Introduction

Bone healing is a remarkable biological process that repairs fractures and restores strength. Whether you’ve suffered a minor crack or a complex break, understanding bone structure and healing phases can help you optimize recovery.

This guide covers:

✔ Bone anatomy (cortical vs. trabecular bone)

✔ Perren’s Strain Theory – why movement affects healing

✔ The 4 stages of secondary bone healing

✔ Primary vs. secondary healing (and when each occurs)

✔ How doctors assess fracture union

1. Bone Anatomy: Cortical vs. Trabecular Structure

Bones are not just solid structures—they have a complex, dynamic architecture that influences healing.

Cortical Bone (Compact Bone)

- Made of tightly packed osteons (Haversian systems).

- Contains central Haversian canals (blood vessels) surrounded by concentric lamellae.

- Volkmann’s canals connect osteons for nutrient exchange.

- Found in diaphyses (shafts) of long bones, providing strength and rigidity.

Trabecular (Cancellous) Bone

- Spongy, porous structure with woven trabeculae.

- Found in metaphyses (ends of bones) and vertebrae.

- Provides shock absorption and supports bone marrow.

🔗 Learn more about bone anatomy from the NIH Osteoporosis Resource Center.

2. How Do Bones Heal? Perren’s Strain Theory

Fracture healing depends on mechanical strain (movement at the break site).

- >10% strain → Forms granulation tissue (no bone growth).

- 2-10% strain → Forms fibrous tissue (scar-like).

- <2% strain → Allows bone formation (optimal healing).

This explains why:

✔ Stable fractures (minimal movement) heal faster.

✔ Unstable fractures (high strain) may need surgical fixation.

3. The 4 Stages of Secondary Bone Healing (Callus Formation)

Most fractures heal through secondary healing, involving four key phases:

First Phase: Inflammation (Week 1)

- Haematoma forms at fracture site.

- Immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages) remove debris.

- Symptoms: Swelling, heat, pain, redness (rubor, calor, tumor, dolor).

2nd Phase: Soft Callus (Weeks 2-3)

- Fibrous tissue & cartilage replace granulation tissue.

- Fracture becomes “sticky”—resists shortening but not bending.

- X-rays may show widened fracture gap (due to bone resorption).

3rd Phase: Hard Callus (Weeks 4-12)

- Osteoblasts form woven bone (visible on X-rays).

- Healing methods:

- Intramembranous ossification (direct bone formation under periosteum).

- Endochondral ossification (cartilage → bone transformation).

- Fracture becomes rigid but not fully strong.

4th Phase: Remodeling (Months to Years)

- Woven bone → Lamellar bone (stronger, organized).

- Follows Wolff’s Law: Bone density increases where stress is highest.

- In children, bones fully remodel; in adults, some deformity may remain.

🔗 Explore fracture healing timelines at OrthoInfo.

4. Primary Bone Healing (Direct Healing Without Callus)

Occurs only with rigid fixation (e.g., plates & screws).

- No callus forms—bone heals directly via osteoclast/osteoblast activity.

- Cutting cone mechanism: Osteoclasts tunnel, osteoblasts lay new bone.

- Slower than secondary healing but avoids soft callus weakness.

5. How Do Orthopedics Know If a Fracture Is Healed?

Healing is confirmed by:

✅ No pain on weight-bearing

✅ No tenderness or abnormal movement

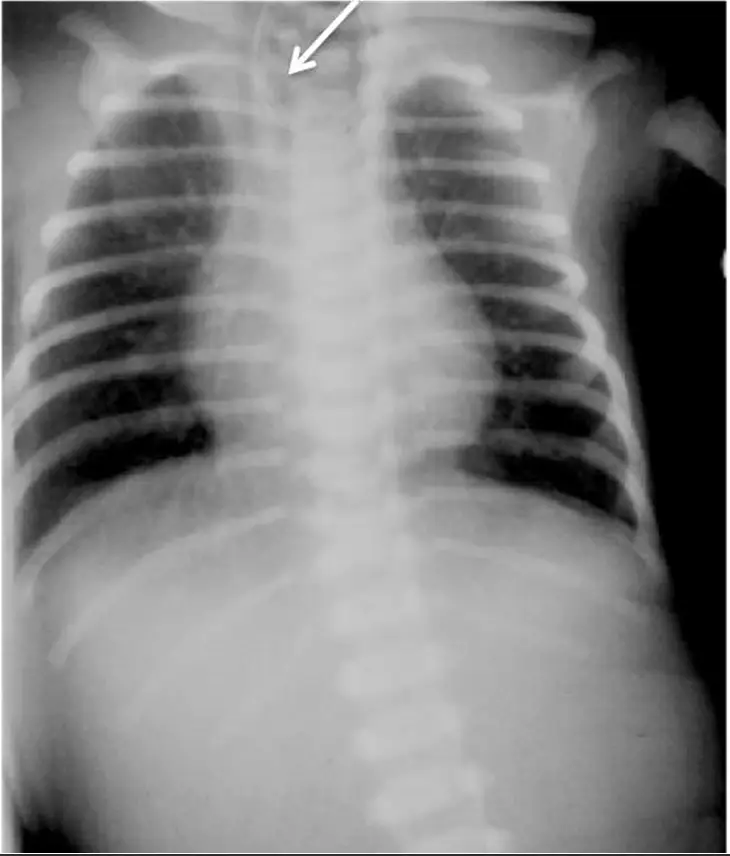

✅ X-ray signs:

- 3/4 cortices bridged (long bones).

- Bridging trabeculae (metaphyseal fractures).

Conclusion

Bone healing is a complex but fascinating process influenced by strain, stability, and biology. While secondary healing (callus formation) is most common, primary healing ensures precision in surgically fixed fractures.

Key takeaways:

✔ Movement affects healing (Perren’s Strain Theory).

✔ Secondary healing has 4 stages (inflammation → remodeling).

✔ Rigid fixation enables primary healing (no callus).

✔ Full remodeling can take years, especially in adults.

🔗 For more on bone health, visit Mayo Clinic’s Orthopedic Guide.

Also read: Fracture assessment and fracture radiological assessement